Vol. 4: Opening Night at Frog Club, from Horses' Liz Johnson

I went to the no-phones restaurant, where you can kiss the chef for $1,000.

I went to the no-phones restaurant. I gazed upon the plates suspended from the medieval chains. I ate the stunningly plush English muffin, griddled in clarified butter, and I wrote up a brief report, which you can read here. (If you’re unfamiliar with the context of this restaurant, I suggest starting there.)

By semi-popular demand, here’s a longer account of opening night at Frog Club. I’ll tell you about the food, and try to dive into questions that attendees and community members are posing around the project.

What was the vibe?

When a place is kept this mysterious, there’s usually a compelling reason. At spots like San Vicente Bungalows and Soho House, photographs are prohibited and discretion is encouraged, nominally to protect the privacy of celebrity customers. In practice, those policies exist to promote the charade of exclusivity. But those are social clubs with restaurants, where food is not the focus. At Frog Club, the secretive new tavern from chef Liz Johnson — whose name you probably recognize from the news coverage last year of her salacious divorce proceedings — food is the focus. For a decade, Johnson has been racking up praise (alongside her former business partner and the other half of the divorcing couple, Will Aghajanian) precisely for putting strange and brilliant spins on ordinary cuisine.

So, why does she want to keep everyone quiet? Well, there’s the scandal — perhaps Johnson wishes to deflect, by stoking the mystery of her first solo institutional project. It would be clever and distracting showmanship. A second possibility is that Johnson wants to protect against the vibe-killing TikTokers who inevitably descend on buzzy new restaurants with ring lights and lavalier mics to pick up real-time voiceover. (The Great Chefs tribute video announcing the official launch does suggest a certain commitment to the lo-fi spoils of yore.) A third could have to do with legal conversations about ownership; as I reported for The New York Times, Aghajanian alleges that Frog Club is “in legal limbo,” and an application for a liquor license I found lists both of their names.

And a fourth might be a reaction to all of the media coverage last year — perhaps Johnson is sending us a message. Perhaps she really would prefer it if we put down our phones, shut our laptops, and ate her soufflés in peace.

As any citizen of the internet in 2024 could tell you, though, attempting to classify the inside of a restaurant is the surest way to get New Yorkers to flock to it.

On opening night, those attempts began at the heavy, arched door of 86 Bedford Street. As fans of Chumley’s — the Prohibition-era speakeasy that occupied the address for nearly a century — we recognized the entrance. But we recognized little else. The uncanny valley set in almost immediately, when we were required to hand over our phones to a friendly man named Tony. He stood at the door in a fur hat with drooping ear flaps, pressing custom-made Frog Club adhesives over all lenses and informing us of the “no photography” policy. So began the warnings of all the ways a diner might get “86”-ed from the restaurant, which managed to condemn social media users and bait them at the same time; other ways included thinking about touching the memorabilia, asking for a free meal, or taking a selfie in the bathroom.

Inside, friends of the house and DeuxMoi targets alike seemed to surrender almost immediately to its exclusivity, relieved to be neutered of their ability to point, shoot, and share. The two windowless dining rooms were wrapped in a sprawling mural of frogs in 1920s clothing, dining on dishes from the Frog Club menu and falling over drunk. An almost laughable number of plates hung from chains overhead, like a bondage den had crossed with a Pottery Barn, and there were amphibians everywhere. There was a giant one hanging among the plates, there was a portrait of one in FDNY dress that a server said was an homage to a former regular who had passed away in 9/11, and there were dozens of them grinning wildly out from the stickers on phones that stuck out from purses and languished on tables. It was like Bemelmans Bar had ripped a few lines of adderall and decided to rewrite Frog and Toad. A little Vegas, a little steampunk, a little delirious. We sat beside the fireplace. I looked up at the circus of color and chain links and tilted objects all around, and felt as though I was glancing up from a 3 a.m. party conversation to realize everyone I knew had already gone home.

In certain clear ways, Frog Club asserted itself as a throwback to Chumley’s. There was the photography policy, which (generously) might have existed when Chumley’s opened in 1922, had there been iPhones to capture its patrons breaking the liquor laws. There was the name, which a historian seated nearby said was a reference to a Marxist reading room that used to exist above the bar.

But, for reasons that don’t begin or end with the scandal that swathes the restaurant, Frog Club turned out to be something else entirely.

Who was there? What were they saying?

In between sips of the Dirty Kermit (your choice of mezcal or vodka, and green tomato, $26) and a Manhattan variation served in an icy stainless steel martini glass ($24), guests — a former creative director of a huge brand, a few food influencers who seemed to have found their way there organically, and some neighborhood locals — watched Johnson navigate the party. She moved calmly, self-possessed in chef whites, in the same green neckerchief she wore in the Great Chefs video, delivering dishes to diners and stopping to pose for a Polaroid photograph with food personality and magician Josh Beckerman. She paused to chat with the filmmaker Ali Asperheim, who has been making a documentary about Johnson.

Amid the wall murals and the buttery Maine lobster pierogies ($27) and all of the murmured talk of the drama that overtook Horses, the opening suggested a restaurant wobbling between intoxicatingly creative and a bit off-kilter. A question seemed to hang in the air: which would prevail?

Quirky details were as plentiful as rumors. (“I heard they’re trying to sell Horses,” one diner said to another between his dinner and dessert. You don’t say.) On the menu of throwback cuisine, beneath items like “Spinach Soufflé, ‘NY, NY’” and “Green Tomato Strings” and the vegetarian entrée called “Bale of Hay” was a line item that read simply, “Kiss the Chef,” for $1,000. As is customary in one of Johnson’s restaurants, dishes began to sell out almost immediately, and menus came stamped with a red “86” beside exhausted items, like the “Baked Beans Henrietta” with foie gras. (Again with the 86s. The pervasive use was a reference to the phrase’s theorized origin at Chumley’s.)

Two red roses which had been, perhaps symbolically dethorned, landed on our table at some point in the meal.

Several diners told me they were rooting for a redemption arc for Johnson, who they felt had taken an unfair amount of heat for a scandal in which they thought her role wasn’t totally clear. At least one invoked the recent rave reviews of Sailor, the new Brooklyn restaurant from April Bloomfield, and her first big public project since the dissolution of The Spotted Pig.

It’s a point of contention across the industry, particularly because the details of the Horses fall-out were messy and, in certain cases, speculative. As Will Ryan, who runs the pop-up Percy’s, wrote to me in an Instagram DM, “I don’t get offended or give a shit about any of the politics but I’m like, should we be showering people who aren’t transparent in press when they could still be bad?”

This sort of thing, of course, comes up all the time. There are artists or filmmakers about whom unsavory rumors surface, and then we must discuss the validity of consuming their art. (Even when the rumors are confirmed, it's not always a different story.) They’re making things, and people are talking about those things, whether or not that analytical energy would be more productively spent elsewhere.

On the back of the dessert menu was a manifesto, reading, “Frog Club is Timberlands in the Winter. Frog Club is dripping window AC units in the Summer. Frog Club is bodegals [sic]; salt, pepper, ketchup. Is chess games in Tompkins Square Park. Is fresh greens from Chinatown. Is missing the L train. It’s not Brooklyn. It’s Manhattan. Frog Club is a meeting place for those interested in new ideas. No windows, no photos, just talk. Here, the customer isn’t always right. Frog Club is brash, but you love it. Frog Club is the New Yorkiest room in New York and it will leave you wondering, what happened at 86 Bedford last night?” It might also leave you wondering what a bodegal is.

“I don’t know if it’s the New York-iest – but I felt like it was New York-y. It felt like real New York,” said Beckerman, the magician. “I knew about the Horses issues, but that had no bearing on eating at Frog Club – if you really know the details, why would it?”

“I honestly should know more than I do about what went down,” said one diner who asked not to be named, because she works in the culinary industry. “But this is her, not him, and I’m excited she was able to get it done.” A few others stated that they had not really heard of Horses, or the scandal that surrounded it.

“It’s a bar, or something, in Hollywood,” said one diner to his companion, who nodded yes. At Frog Club, the customer isn’t always right.

How was the food?

What happened at Frog Club was never really destined to stay at Frog Club, despite the photo policy. You’re here because you want to know about the food. Was it redemptively good? What might that even mean?

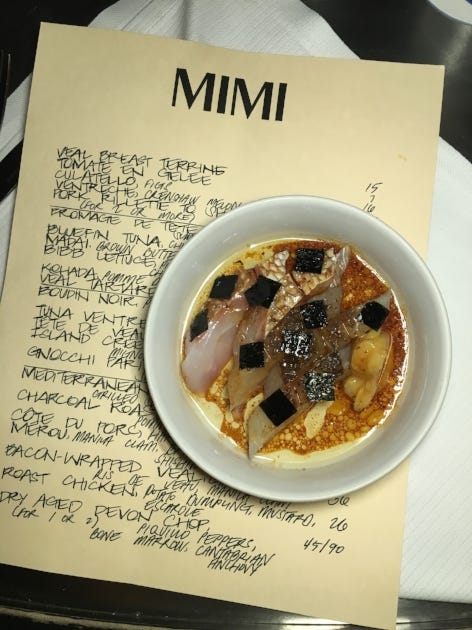

I’d been following Johnson’s eccentric, flavorful plates since the boudin noir and the sliced Madai served in brown butter with lemon curd at Mimi, through the cornish hen panzanella at Horses. Though it occurred to me on Wednesday night that I would have had no way of knowing which bits, specifically, came from her – maybe it didn’t matter.

The menu fit neatly into our current national nostalgia craze, with a spinach soufflé and a $22 plate of wings, and tapioca pudding for dessert. But there was a certain amount of whimsy that felt specifically young and hip (Johnson is 33), as with the sort of trompe l'oeil, Lisa Frank, Spaghettieis-evoking “Tutti Frutti Spaghetti SundaeTM” ($16), or the side of whipped butter served with the burger.

Many tables murmured happily as they polished off plates of “The Original Greenwich WingsTM” ($22), which were tossed in a subtle version of buffalo sauce. They were delicate and buttery, though diminutive — I suspect they were wing tips of the cornish hen pieces that came out as the “Roast Chicken Dinner.”

Pierogies ($27) came stuffed with shreds of Maine lobster, with thinner, slightly gummier casings than you’d find on the pierogies at Veselka, tossed in browned butter. Contemplated as pierogies, they fell a little flat, but I would have been thrilled to see them arrive at my table after I’d ordered lobster mezzelune. They delivered a satisfying dose of nursery-food-energy; I just wished the dough had been forced into a few more minutes of gluten development before it was rolled and stuffed. “Green Tomato Strings” ($16) turned out to be onion ring-ified tomatoes, and they were a commendable drinking snack when paired with one of the impressive glasses of white wine. The spinach soufflé ($26) puffed proudly several inches above its rim, eggy and soft, with a vaguely cheesy microcrust.

A hamburger ($34) was juicy but a bit under-seasoned (an easy fix), though its true selling point was its bun, a clarified butter-griddled English muffin made by Krizia Villaflor. The English muffin’s height alone had me reaching for my taped-up phone. The “Roast Chicken Dinner” ($44), a pile of crisp cornish hen parts with a neat pyramid of herbed rice and a dish of cranberry jelly, made its way to lots of booths. The meat was tender, though scarce on the little limbs — a perfect harbinger of Ozempic-era dining — and the mustard-crème fraîche sauce over the top was bright and rich; it might’ve been my second favorite thing, after the English muffin. The plate of twisted French fries was underwhelming, though it came with Heinz ketchup, which would spruce up any fry.

For dessert, the banana chiffon pie ($16) was light with a flawless Americana cookie crust. The pie itself had a pronounced fruity flavor, though its bottom layer was a bit too stiff with gelatin. Instagram personality Mike Chau, who was in on opening night, wrote to me that he enjoyed the burger and the soufflé. “Most ironic is the total influencer catnip Spaghetti Sundae that you’re not allowed to take pictures of!” he said.

Johnson appeared to have been thoughtful about creating a venue and menu that were distinctively hers in the wake of… everything. And yet a few dishes maintained faint culinary through lines to her last few projects with Aghajanian. The seafood pierogies recalled a tagliarini with clams at Horses; all the butter brought back Mimi. But it was obvious that Johnson had made a real attempt to create a new mythology about the way she feeds people. Which might be the true answer to why there’s so much smoke and mystery, why there are so many things you’d want to take a photo of, which Johnson won’t let you capture. The sarcastic titling and plating, all of the TMs and the 86s, the paper hats, the towering diner-style slices of pie. And despite the self-consciousness of this edginess, she created something strangely compelling.

Was it outstanding? No single dish blew my mind or had me wondering how she did it (after one of my first meals at Mimi I became obsessively devoted to trying to reverse engineer her Parisian gnocchi) — but it certainly had promise. A frog ready to be kissed.

This essay was everything I hoped it would be!

Ella... please write a book....! This was exactly what I wanted and I would like to never be through with it